A ferry is plying its trade on Lake Constance between Friedrichshafen in South German and Romanshorn in North Switzerland:

Southern Germany

The amazing automatic popcorn machines of Switzerland and Germany

We’re under attack! It seems these machines are now literally all over Southern Germany and Northern Switzerland! By which I mean, to date, I’ve seen two of them: one in Friedrichshafen (Germany) and one in Winterthur (Switzerland) – the latter at my local grocery store, no less.

They work like this. You deposit either a 2 EUR coin (if you are in Germany) or a two 2 CHF coins (if you are in Switzerland),

and in just 2 minutes you’ll have a little paper container of freshly popped popcorn (sweet or salty, your choice).

How does it taste? I found the kernels to be better that what you’d get at home with microwave popcorn, but not quite as good as the popcorn they serve at movies. And there was a faint taste of oil – but a type of oil I’m not used to tasting. It wasn’t bad, just different.

Did I accidentally discover a new Einstein?

I am not the world’s biggest fan of museums, but I had a frightening, emotional reaction at the Einstein Museum in Bern, Museum, when I looked at this grammar school photo of Einstein’s class:

My reaction was frightening and emotional, because all of the dozens of schoolchildren at staring emotionless and straight faced at the camera, with only one notable exception: the young Einstein is smiling:

Interestingly, I’ve noticed this one time before. At a large Indian wedding a group of small children asked me to take their picture with my digital camera. After reviewing the picture some years later, I realized that only one of the children was smiling:

Could it be my path crossed with the next Albert Einstein?

Schwabian Fish

A big schwabian fish in a stream next to the amazing Baroque cathedral at Zwiefalten,

Two AMAZING ways that old meets new!

This is the Münster, a Catholic cathedral in the Middle Age village of Villingen in Southern Germany:

It dates back to the year 1130. It is very, very old.

And this is one of the doors of the cathedral:

Created in the late twentieth century out of bronze by the artist Klaus Ringwald, it is very very new.

So you might think: old meets new. And you’d be right.

But . . . you’d only be half right!

Because the scenes on the massive bronze door (twelve of them, no less) depict historic scenes from the Old Testament (left) and the New Testament (right).

So . . . this is two amazing ways that old meets new!

The Neckar in Tübingen

Black Forest Trees

These are some trees in the Schwarzwald of Southern Germany, just outside of Freundenstadt:

I read two interesting things, but I don’t know if they are true.

First, there are no original trees in the Black Forest. All of the original trees have long, long been harvested and re-planted.

Second, the current trees of the Black Forest are no longer optimal for the current climate conditions, so land management experts in Germany are considering replacing the trees with different species that are better suited to warm temperatures.

Villinger Gargoyle – and an unbelievable language gap

I spotted this gargoyle in the historic Middle Ages Southern Germany village of Villingen-Schwenningen:

But then something amazing happened! I realized I did not know the German version of this word, so I looked it up: der Wasserspeier.

OK, fair enough. Gargoyles were primarily designed to direct the flow of rainwater off of a building.

But here’s the amazing part: in English, the word gargoyle immediately invokes terrible emotions involving monsters and demons and people with ugly faces – whereas (I’m pretty sure) the word Wasserspeier does not. In fact, just about any native speaker would define gargoyle as monster – not as e.g. water spout.

I’ve often thought that the German word for battle, die Schlacht, is a good example of this in the opposite direction: battle connotes fight in English, but in German it connotes slaughter.

The mystery of the Middle Ages dormer cranes – solved!

In earlier blog posts I’ve mentioned that some – but only some – Middle Age villages have cranes on their dormers, like this:

and like this:

The cranes are obviously for hauling loads to the top of the building.

But here’s the mystery: if these cranes are very useful, and indeed they appear to be, then why don’t more Middle Age villages have buildings with such gable-cranes?

I recently learned the answer from a tour guide in Villingen-Schwenningen: ground water! In the Middle Ages it was preferred to store grain and food underground, in cellars. But in villages where this was not possible, due to a high ground water table, it was stored on the highest (and architecturally, less useful) part of the building. Therefore, if you spot a dormer crane it generally means high ground water!

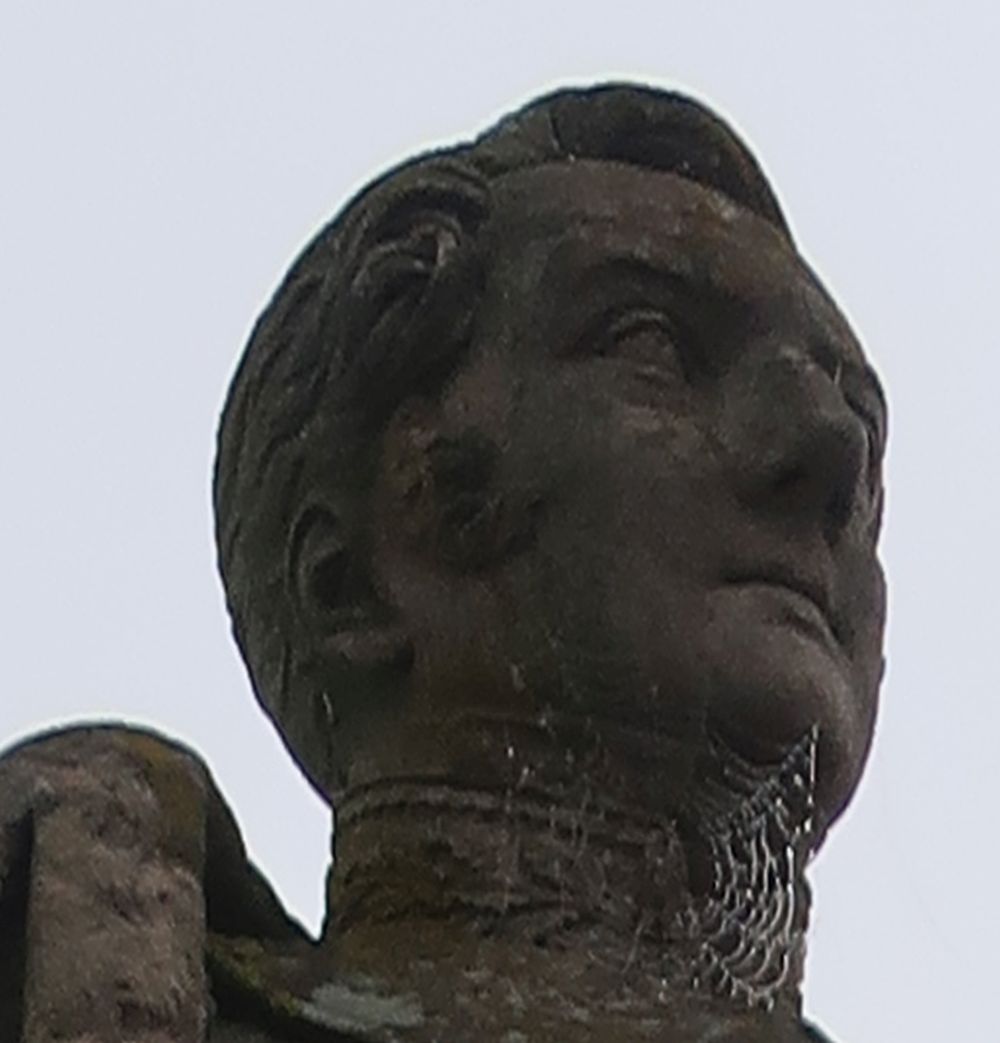

Stone sculptures in Villingen

Continuing the series, the historic walled village of Villingen-Schwenningen in South Germany has a stone sculpture just inside the wall:

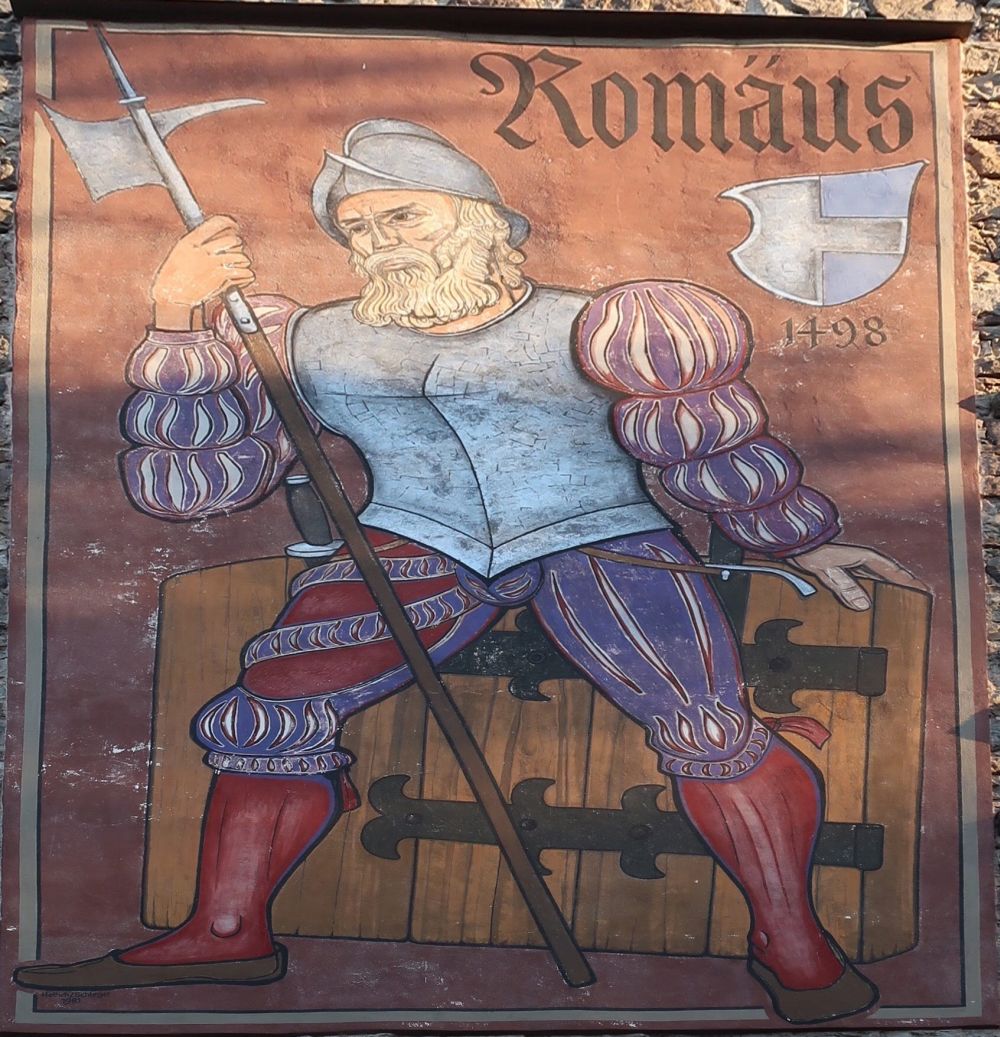

Romäus, unstretched

I was on a guided tour of the historical South German village of Villingen-Schwenningen last week when I learned that the local town hero was a man named Romäus, their version of Paul Bunyan. His image is painted on one of the tower gates of the village wall:

The story goes that he travelled to the neighboring village of Rottweil, stole the massive, multi-ton doors to their village, and walked all the way back to Villingen, carrying the doors with him, no less!

As a tribute to the many friendly townpeople I met, I used Microsoft Lens to unstretch him!

According to Wikipedia, just like Paul Bunyan there are many stories, but here’s the one on the wall:

The Mighty Bishops of Konstanz – and a Duke?

If you go to the German city of Konstanz you’ll find some imposing statues along the Rhine River:

OK, so let’s have a quick look at who these guys were. Unbelievably, three of them are bishops that lived and died a long, long, long time ago.

Here is Bishop Berthold, who died in 1078:

Here is Bishop Gebhard, who died in 995:

And finally, here is Bishop Conrad, who died in 975:

But who is the fourth guy? It’s Leopold, the Grand Duke of Baden, who died quite recently, in 1852:

Quite an interesting conundrum. Was this a vanity project commissioned by the Duke before he died, to have his statue next to these old guys?

Somebody must know – but not me!

Aquaforming

I am not really sure if aquaforming is a word. I’m talking about the terraforming of streams, like this example in Algäu, Germany, shows:

I think just about everyone has seen numerous examples of this in just about every country. But, if you stop to think about it, when / where / who decided to add this to any given stream?

In some (wonderful) cases, there is documentation nearby. There are some incredible examples of this in Germany’s Schwarzwald, or Black Forest, where the villages undertook massive terraforming projects to project the villages against torrential flooding.

And if you go hiking in the forests around Stuttgart, you are likely to encounter dry man-made canals, empty brick-lined reservoirs, and stone bridges over nothing – all the features of a sophisticated water abatement system that sits quietly for most of the year, and really only comes into its own during a downpour.

I’ll post some snaps of these as time permits.

The amazing self-service flower stands of Germany and Switzerland

I’ve seen these things for years – but like so many things, I only just realized that for Americans this concept might be kind of strange.

The countrysides of Germany and Switzerland are filled with little “self-service” stands owned by local farmers. You can stop anytime and get flowers, vegetables, and sometimes even eggs. There’s a little jar for you to put your money, and it run 100% according to the honor system.

I took this snap of a flower stand just outside of the Northern Swiss village of Embrach:

The amazing garbage vacuums of Germany – IN ACTION!

I’ve recently blogged about the garbage vacuums in Germany. So you can imagine my thrill and pleasure when I got the privilege to photograph one in action!

As you can see, even the small children took a small break from their very busy day to watch the two men.

And you can be sure to expect no less than ultra-cleanliness from the South Germans, so after sucking out the garbage, the big orange van is equipped with a high temperature steam sprayer, and the whole area is steam cleaned.

My guess is that the entire process, from driving up to the garbage area, sucking out the garbage, and steam cleaning it – the entire process took no more than 7 or 8 minutes.

Unbelievable!

Burg Hollenzohlern

Bodensee Castle

A view of the castle from below:

Bodensee Stork

I’ve written many blogs about storks, and this is my latest snap, taken at the Franciscan cloister of Hegne just across from the Southern German village of Allensbach:

Bodensee Skink

This little fellow is not an unusual sight in Southern Germany; I took this snap in the tiny hamlet of Hegne next to the village of Allensbach:

There are some people who would refer to this little guy incorrectly as a Blindschleich, or blind worm – but you can see from his fine peeper’s that he’s anything but blind.

Thirty Years’ War

At least I suspect it is, painted here on the inside of a small wooden hut for hikers nestled deep within the Schwabian Alb:

The Thirty Years’ War (Dreissigjähriger Krieg, in German) lasted from 1618 to 1648. If you look closely at the coats of arms, you’ll see Baden on the left, and Württemberg on the right:

But to be honest, this is just a semi-educated guess. If you have any better info, do let me know!

Germany’s highest bridge

This is it, from a close-up viewpoint:

And this is it, from an artistic viewpoint:

And this is it, from a viewpoint where you can really appreciate how tall it is:

Finished in 1979, this is the Kochertalbrücke (Kocher Valley Bridge), and at 178 m (or 574 feet) it was, until 2004, the highest bridge in Europe. Remember that the Golden Gate Bridge, in comparison, is only 220 feet, so this bridge is just over double the height.

If you like photographs of bridges, you’ll find a number of them that I’ve tried to capture in my blog.

What I find totally amazing about this bridge is the complete silence underneath it. The traffic deck is so high in the air, none of the sounds of the passing vehicles can be heard from the ground.

Unbelievable bridge in Southern Germany

I’ve driven across this bridge hundreds of times, but recently I stopped underneath to take some pictures.

This is the Neckar Viaduct up close:

And this is the Neckar Viaduct, somewhat further away:

What’s just amazing is that this viaduct has a height of 125 meters, or just over 400 feet. In comparison, the more famous Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco has a height of only 67 meters or around 200 feet. That means the Neckar Viaduct is almost twice as high as the Golden Gate Bridge!

Stuttgart Crane

Continuing the series,

Meteorite in Southern Germany – or is it?

This object caught my attention when I was visiting Southern Germany, not the least because of the way the concrete was depressed on one side and elevated on the other:

However, after walking around a bit I found this plaque on on the ground:

So, it appears to be work of art and not an actual meteorite!

The great volcano fields of Southern Germany

When people think of Germany, not a lot of people think about volcanos. But in fact, Southern Germany has a region called Hegau that is dotted with dozens exposed and extinct volcanos. This snap shows just a few of them:

A few of them are topped with the ruins of medieval castles, and I’ll post further snaps as time permits.